Article

The New Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines: An In-Depth Guide

Author(s):

New atrial fibrillation treatment guidelines from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology clarify the role of novel oral anticoagulants and rate/rhythm control medications.

New atrial fibrillation treatment guidelines from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology clarify the role of novel oral anticoagulants and rate/rhythm control medications.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) may ask about the new guidelines issued by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC). These new guidelines, copublished online on March 28, 2014, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation, discuss the role of evolving treatment strategies and new drugs in patients with AF, based on the most up-to-date scientific evidence. The new guidelines replace the previous recommendations—the 2006 ACC/AHA/ESC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and 2 incremental updates to that guideline, the last of which was published in 2011.

Key Points:

- Risk scoring using the CHA2DS2-VASc score and patient preference based on the risks and benefits of therapy should help decide whether or not to initiate anticoagulation.

- Warfarin is still the only recommended therapy in patients with mechanical heart valves, and use of dabigatran is specifically not recommended in patients with mechanical heart valves.

- Patients with nonvalvular AF have a choice among warfarin and the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs).

- The level of evidence supporting use of NOACs is lower (level B) than warfarin (level A), but use of warfarin requires more monitoring.

- Monitoring in patients taking warfarin should include an international normalized ratio (INR) level measured at least every week when starting therapy and at least every month after achieving a therapeutic INR (usually 2.0 to 3.0).

- When patients taking an anticoagulant (either warfarin or a NOAC) are preparing for surgery, some patients (eg, those with mechanical heart values or those with high cardiovascular risk) may require temporary replacement of antithrombotic therapy with unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin.

- Patients who fail to maintain a therapeutic INR with warfarin should receive a NOAC.

- Because data on NOAC safety and efficacy (even at reduced doses) is lacking in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment, NOACs require, at minimum, yearly monitoring of renal function.

- Patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease and patients undergoing hemodialysis should receive warfarin instead of a NOAC.

- Patients with infrequent episodes of AF may continue to use long-term therapy for AF with an antiarrhythmic drug, but patients with permanent AF should not receive long-term therapy with antiarrhythmic drugs for rhythm control. Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and beta blockers are antiarrhythmic drugs, but offer rate control (not rhythm control) so these drugs can still be used long term in patients with permanent AF.

- For patients with infrequent, well-tolerated recurrences of AF who are receiving maintenance therapy with antiarrhythmic drugs, amiodarone may be used after failure of other antiarrhythmic medications (eg, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers or beta-blockers) due to the potential eye, liver, and thyroid problems that may arise with amiodarone use.

- Patients with permanent AF using dronedarone are at increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular death. As a result, use of dronedarone in patients with permanent AF is not recommended. In addition, dronedarone should not be used in patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure, or in patients who have had an episode of decompensated heart failure within the past 4 weeks.

- For patients undergoing electrical shock (electrical cardioversion) to break the pattern of the abnormal AF rhythm and restart the heart’s normal sinus rhythm, guideline authors recommend attaining a therapeutic INR level for at least 3 weeks before and 4 weeks after the cardioversion procedure to reduce the risk of dislodging a thrombus after cardioversion.

- In patients with AF or atrial flutter of less than 48 hours' duration who also have a high risk of stroke, immediate cardioversion may be necessary; anticoagulation with heparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin (eg, enoxaparin), or a NOAC may be used immediately before cardioversion and afterwards long-term anticoagulation therapy should be initiated.

- In some cases, when immediate cardioversion is necessary, a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) may help the physician detect clots in the heart before proceeding with cardioversion.

- The guidelines mention several exceptions and therapeutic considerations for patients with certain disease states (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, AF complicated by acute coronary syndrome, hyperthyroidism, pulmonary diseases, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, pre-excitation syndromes, heart failure, familial AF, and patients who have undergone cardiac surgery).

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a condition of uncoordinated contractions of the ventricles and atria of the heart that may lead to pooling of blood in the atria and ventricles of the heart, leading to clot formation. These clots can then travel to the brain and other parts of the body, increasing the risk of stroke. Available treatments include rate and rhythm control, electrical cardioversion, and anticoagulation. With the approval of 3 new oral anticoagulant agents in recent years, the new guidelines clarify the role of these agents and update the role of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with AF.

Diagnosis, Risk Factors and the Decision to Initiate Treatment

Several risk factors increase the risk of AF, including conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, hyperthyroidism, thickening of the left ventricle, heart failure, having undergone cardiothoracic surgery, and a prior myocardial infarction (MI). In addition to comorbidities that increase the risk of AF, abnormalities in certain biomarkers (eg, B-type natriuretic peptide, C-reactive protein), genetic factors (eg, European ancestry, family history), and lifestyle factors (eg, alcohol use, smoking, and exercise) may also increase the risk of developing AF.

Risk factors alone and clinical suspicion are not sufficient for diagnosis of AF. Even in patients with several risk factors who are highly likely to have AF, an electrocardiogram is always necessary to establish the diagnosis. AF may be classified as paroxysmal (abnormal rhythm terminates in <7 days), persistent (abnormal rhythm continues for >7 days), or permanent (a decision has been made to stop attempting to reestablish normal sinus rhythm).

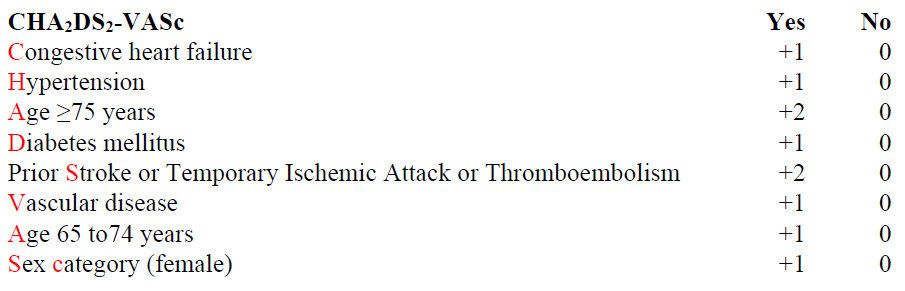

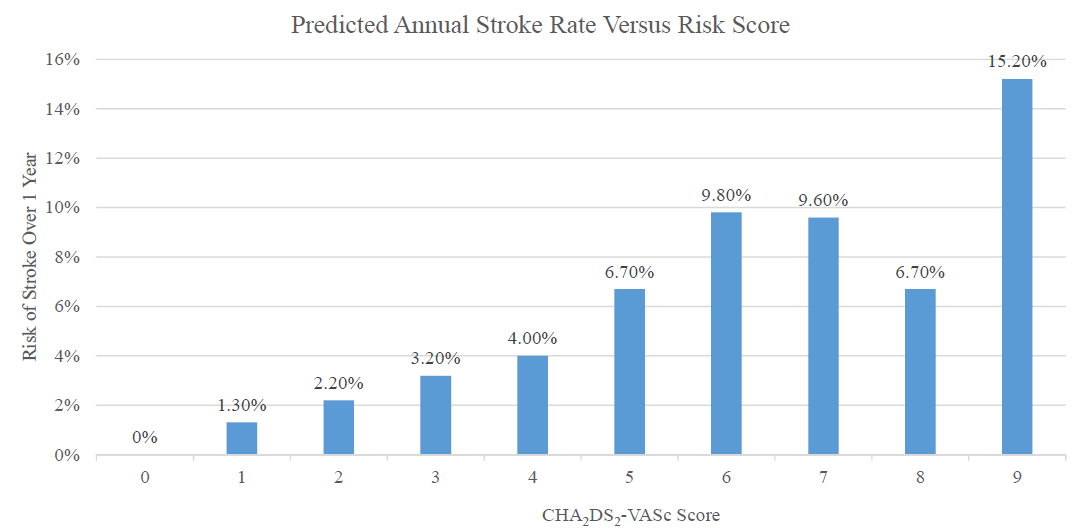

After diagnosis, physicians may use the CHA2DS2-VASc score (see Table 1 and Figure 1) to help select patients who are appropriate candidates for anticoagulation therapy. For instance, in patients with nonvalvular AF with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0, no treatment is recommended, but with a score of 1, an oral anticoagulant or aspirin may be considered, while a score of 2 or greater may necessitate treatment with warfarin or a NOAC.

Table 1:

Figure 1:

Treatments: Anticoagulants

Warfarin is still the only recommended therapy in patients with mechanical heart valves (and dabigatran is specifically not recommended in patients with mechanical heart valves). In patients with nonvalvular AF, however, a variety of therapeutic options now exist in addition to warfarin, including dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban. As a group, these are known as novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs).

In the guidelines, the evidence supporting use of NOACs is rated lower (category B) than the evidence supporting warfarin use (category A). Despite the slightly lower level of evidence supporting use of NOACs, the guidelines point out that considerable monitoring requirements must be met for effective use of warfarin.

In addition to the need for additional anticoagulation early in treatment for some patients, warfarin therapy requires monitoring of the international normalized ratio (INR) at least once a week until a therapeutic INR is attained. Even after attaining a therapeutic INR, the guidelines recommend INR monitoring at least once monthly during maintenance treatment.

Although some patients may do well on warfarin, many patients fail to achieve and maintain consistent therapeutic INR levels. In these patients, the guidelines now recommend use of NOACs. The new guidelines also clarify the importance of monitoring in patients taking NOACs—an issue that had been unclear since the introduction of these agents. The new guidelines recommend reevaluation of renal function in patients using NOACs at least once per year.

Renal function monitoring is important in patients taking NOACs because, in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease, warfarin may be a safer option than NOACs.

Under the new guidelines, warfarin is preferred over NOACs in patients undergoing hemodialysis or in patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease (ie, creatinine clearance [CrCl] <15 mL/min).

In addition, although NOACs may be used in patients with moderate-to-severe CKD at reduced dosages, safety and efficacy have not been established in patients with moderate-to-severe CKD. For some patients with moderate-to-severe CKD, warfarin may still be the best choice.

Rate Control

Before attempting surgical procedures to control AF, such as AV nodal ablation, the guidelines recommend pharmacologic therapy. For instance, at first, beta blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers may be used to help control ventricular rate in patients with AF, including patients with paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent AF.

Patients with infrequent episodes of AF may continue to use long-term therapy for AF with an antiarrhythmic drug for rhythm control, but patients with permanent AF should not receive long-term therapy with antiarrhythmic drugs for rhythm control. It is important to note that antiarrhythmic drugs for rate control may still be used in patients with permanent AF.

The new guidelines recognize that amiodarone may cause thyroid problems, liver problems, and eye problems, and should only be used after other agents have failed to control AF, or if use of other agents is contraindicated.

Just as amiodarone is not recommended as a first option in most patients with permanent AF, its sister drug dronedarone is also not recommended. Patients with permanent AF using dronedarone are at increased risk of stroke, MI, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular death.

The guidelines now recommend agents other than amiodarone and dronedarone for many patients with AF. Other agents, in this context, include beta blockers titrated to a dose high enough to reduce a patient’s resting heart rate to <80 beats per minute, or in some cases (primarily patients who have AF but do not have symptoms of AF), <110 beats per minute. However, the guidelines note some important caveats before use of antiarrhythmic drugs in certain groups.

For instance, nondihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists (ie, extended-release diltiazem or verapamil), may increase the risk of hemodynamic instability in patients with decompensated heart failure, and should not be used in these populations. Guidelines also recommend against use of digoxin, nondihydropyridines, and intravenous amiodarone in patients with AF and pre-excitation. Use of these medications may increase the risk of ventricular fibrillation (a potentially fatal emergency heart rhythm disturbance) in patients with AF and pre-excitation.

Rhythm Control: Electrical and Chemical Cardioversion

Hemodynamically unstable patients may need an electrical shock (electrical cardioversion) or infusion of an antiarrhythmic drug (chemical cardioversion) to break the pattern of the abnormal AF rhythm and restart the heart’s normal sinus rhythm. Caution is warranted, however, because cardioversion may dislodge a thrombus from the heart, potentially causing a stroke. In general, patients who have had symptoms of AF or atrial flutter for <48 hours and who have a high cardiovascular risk receive immediate electrical or chemical cardioversion, whereas patients with symptoms of AF or atrial flutter of >48 hours’ duration or unknown duration receive a course of anticoagulation before undergoing cardioversion.

In patients with atrial flutter or AF that has already lasted more than 48 hours (or when the duration of symptoms is unknown), the guideline authors recommend attaining a therapeutic INR level for at least 3 weeks before and 4 weeks after the cardioversion procedure to reduce the risk of dislodging a thrombus after cardioversion.

In patients with atrial flutter or AF with a duration <48 hours and who have a high stroke risk, or in patients with a high risk of stroke who develop AF or atrial flutter, immediate cardioversion may be necessary. In these cases, anticoagulation with heparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin (eg, enoxaparin), or a NOAC may be used immediately before cardioversion to reduce the risk of dislodging a clot. After cardioversion, in these patients, long-term anticoagulation therapy should be initiated.

In some cases, when immediate cardioversion is necessary, a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) may help the physician detect clots in the heart. If clots are detected, the physician may decide not to proceed with cardioversion.

Rhythm Control: Chemical Cardioversion

Pharmacologic agents with the best evidence of efficacy in chemical cardioversion include dofetilide, flecainide, propafenone, intravenous ibutilide, and amiodarone (although amiodarone is not recommended as strongly as the other agents). Outside of the hospital setting, either propafenone or flecainide may be used to terminate paroxysmal AF in some patients, although these patients must have previously received propafenone or flecainide to terminate paroxysmal AF in a monitored setting. Similarly, although, dofetilide is an oral medication that may be used to terminate paroxysmal AF, the first dose of dofetilide should not be administered outside of a hospital setting due to the risk of QT prolongation and torsades.

Special Populations

The new guidelines make a variety of other recommendations for patients with AF who also have certain other conditions. These conditions include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, AF complicated by acute coronary syndrome, hyperthyroidism, pulmonary diseases, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, pre-excitation syndromes, heart failure, familial AF, and patients who have undergone cardiac surgery. Discussion of these special populations is outside the scope of this guideline summary. Please consult the guidelines for information on specific recommendations for these patient populations.

Conclusion

The new guidelines in atrial fibrillation clarify the role of NOACs in the reduction of stroke risk in patients with AF. The guidelines also recommend against use of amiodarone as a first-line therapy in patients with AF, favoring nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and beta blockers as a first-line choice for pharmacologic control of AF. Understanding the new guidelines and explaining the recommendations of current guidelines is an important priority for pharmacists.

Author’s note: This article is a summary for informational purposes only, and is not intended as a substitute for the full 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation.

Resources:

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014.

Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114(7):e257-e354.

Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(11):e101-e198.

National Institutes of Health. What Is Atrial Fibrillation? www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/af/. Accessed April 2014.

Sethi KK, Dhall A, Chadha DS, Garg S, Malani SK, Mathew OP. WPW and preexcitation syndromes. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;(55, suppl):10-15.

CORDARONE (amiodarone HCl) [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Pfizer Inc; 2011.

XARELTO (rivaroxaban) tablet [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2014.

PRADAXA (dabigatran etexilate mesylate) [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2014.

ELIQUIS (apixaban) [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2012.

Newsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.