Publication

Article

Pharmacy Times

Roll Up Your Sleeves: Adult Immunizations

Author(s):

Compliance with most adult vaccine recommendations is still low due to financial and informational barriers.

Compliance with most adult vaccine recommendations is still low due to financial and informational barriers.

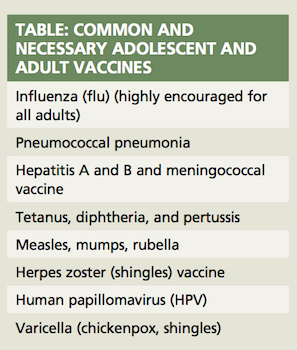

Vaccines prevent many common diseases, including influenza, hepatitis B, herpes zoster, human papillomavirus, tetanus/diphtheria/pertussis, and more recently, pneumococcal infections and shingles. Nearly 50,000 adults die each year in the United States from 1 of the 12 vaccine-preventable diseases identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).1 The US Department of Health and Human Services’ Healthy People reports have identified poor uptake of effective vaccines among adults as a problem for decades.1 Immunizations save lives (Table).

To understand the problem’s scope among adults, one can look first at immunization’s impressive uptake among childhood. More than 90% of children receive all ACIP—recommended vaccines.2 The reasons are 3-fold:

- Pediatricians consider vaccination a practice priority,

- All insurances cover pediatric vaccines so there is no associated cost, and

- Since the 1970s, public schools have required proof of vaccination from all students.

Once patients become adults, vaccination adherence drops precipitously. Compliance with almost all adult recommendations is lower than 40%.3 Why are adult vaccination uptake rates so low? Among adults, many barriers exist. They can be classified as operational, financial, or informational.

Adult Immunization Barriers

Operational barriers are mind-boggling. The American health care system lacks an effective adult vaccine delivery system. Vaccination remains a low priority for both physicians and patients. Unlike schools, employers rarely require proof of vaccination as a condition of employment, so that motivator disappears in young adulthood. Vaccination is covered but optional for adult Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.4 In addition, vaccine availability has been a sporadic concern. Physicians’ offices may have insufficient facilities (eg, refrigeration or shelf space) to store them. Waste is a serious concern; each year, health care facilities return or destroy millions of doses of influenza vaccine. In 2008, about 29 million vials were discarded.5

Financial barriers can be significant for adults who want to be immunized. Coverage varies among private insurance plans, with many omitting coverage for recommended adult vaccines. Those that cover vaccines often have deductibles and copayments high enough to discourage uptake. In the public sector, state and local governments determine coverage and in 2006, only 22 states covered adult vaccines.6,7 Most Medicaid plans cover adult vaccines, but physician reimbursement varies widely and may not reimburse all physician-incurred costs. For elders, Medicare part B influenza, hepatitis A and B, shingles, and pneumococcal immunization, but physician reimbursement again may fall short of all expenses related to administration, creating a disincentive to push vaccination.5

Informational barriers are immense. Most adult patients—and many physicians and other health care clinicians—are unaware of ACIP’s adult immunization recommendations. They may not realize the merits of immunization. And vaccination schedules for adults are more omplicated than those for children, and vary by age and comorbidity. The schedule, located at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/mmwr-adult-schedule.pdf, is a tri-color, heavily footnoted, double-tabled page that takes a bit of time to navigate. Rather than reproduce it here, we refer you to the document since it changes often.8

Immunization records are notoriously incomplete for adults. Immunizers frequently cannot find documentation about patients’ immunization status, must look in multiple places for it, or must rely on patients’ often inaccurate self-report. Health care providers—unaware that immunizations are needed—miss opportunities to educate and vaccinate patients, too.5,9-11

The information aspects of immunization at the patient level are serious. Many patients, oblivious that they need vaccinations, don’t ask for them when they seek health care. Some are fearful of vaccines or needles, and myths about vaccines are plentiful. are plentiful. They may have language barriers or cognitive issues that prevent them from understanding. The whole idea of the need for booster doses is often difficult for patients to understand, and without a structured reminder system, they forget. And, some patients believe they are so old, prevention is no longer a concern.12-14

Rolling Up Our Sleeves

To get patients to roll up their sleeves, health care clinicians need to roll up their sleeves and focus on immunizations. To heighten awareness, several groups have created programs and informational campaigns.

Pharmacists and Immunization

Pharmacists have proved to be leaders in improving immunization rates.4,7,15,16 Patients’ trust of pharmacists and pharmacists’ accessibility in the community combine to make immunization less onerous. Pharmacists can:

- Lead by example by receiving age-appropriate immunizations. Talking about it encourages others to follow suit.

- Become immunizers if their state and local governments allow it. Advertising this service increases foot traffic in the pharmacy and vaccine uptake.

- Post information and offer handouts on adult immunization in highly visible areas.

- Dispel myths (“No, you will not get the disease, even a mild form, from the vaccine,” and “Current vaccines cause fewer side effects and hurt less than older types.”).

- Provide shot records and help patients keep them current.

- Stay abreast of vaccine changes and shortages, and educate patients and other health care professionals.

Conclusion

Allowing pharmacists to immunize patients is a great step forward for pharmacists—and pharmacists have skill sets that we need to use and advertise—and it’s a great step forward for public health as well. The area of greatest need is in the adult community, where immunization uptake is low.

Let's roll up our sleeves and improve the situation!

Ms. Wick is a visiting professor at the University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy and a freelance clinical writer.

References:

- Partnership for Prevention. Strengthening adult immunization: a call to action. www.prevent.org/Topics/Immunization-Policy.aspx. Accessed February 13, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Statistics and surveillance, children, 2011 table data. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nis/data/tables_2011.htm#overall. Accessed February 13, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Statistics and surveillance, adults, 2007 table data. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nis/default.htm#nisadult. Accessed February 13, 2013.

- Lam S, Jodlowski TZ. Vaccines for older adults. Consult Pharm. 2009;24:380-391.

- Marks S. Adult Immunization: The need for enhanced utilization, 2009. www.scribd.com/doc/37159547/Adult-Immunization-The-Need-for-Enhanced-Utilization. Accessed February 13, 2013.

- Orenstein WA, Mootrey GT, Pazol K, Hinman AR. Financing immunization of adults in the United States. Nature. 2007;82:764-768.

- Wu LA, Kanitz E, Crumly J, D’Ancona F, Strikas RA. Adult immunization policies in advanced economies: vaccination recommendations, financing, and vaccination coverage [published online January 25, 2013]. Int J Public Health.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization schedule. http://tinyurl.com/azs2c6f. Accessed February 13, 2013.

- Ladak F, Gjelsvik A, Feller E, Rosenthal SR, Montague BT. Hepatitis B in the United States: ongoing missed opportunities for hepatitis B vaccination, evidence from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, 2007. Infection. 2012;40:405-413.

- Yeung JH, Goodman KJ, Fedorak RN. Inadequate knowledge of immunization guidelines: a missed opportunity for preventing infection in immunocompromised IBD patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:34-40.

- Hernandez B, Hasson NK, Cheung R. Hepatitis C performance measure on hepatitis A and B vaccination: missed opportunities? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1961-1967.

- Kennedy LH, Pruitt R, Smith K, Garrell RF. Closing the immunization gap. Nurse Pract. 2011;36:39-45.

- Kassianos G. Vaccination for tomorrow: the need to improve immunisation rates. J Fam Health Care. 2010;20:13-16.

- Tabbarah M, Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, et al. What predicts influenza vaccination status in older Americans over several years? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1354-1359.

- Taitel M, Cohen E, Duncan I, Pegus C. Pharmacists as providers: targeting pneumococcal vaccinations to high risk populations. Vaccine. 2011;29:8073-8076.

- Lin CJ, Zimmerman RK, Smith KJ. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal and influenza vaccination standing order programs. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:e30-e37.

Newsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.