Article

Pharmacists Play a Crucial Role When Addressing Health Literacy

Author(s):

Providers who are sensitive to health literacy have contributed to positive quality improvement across various institutions.

The idea of health literacy was first described in health care publications in the 1990s.1 It was limited to a patient’s ability to self-manage their health through various skills, such as reading or numeracy. Over the past several decades, research has shown health literacy is a critical determinant of health equities and poor health outcomes. The World Health Organization has expanded the definition to mean more than “… being able to read pamphlets and make appointments. By improving people’s access to health information, and their capacity to use it effectively, health literacy is critical to empowerment.”2

Health literacy is the ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions. Health literacy is extremely pertinent when promoting healthy people and communities. Staggering statistics show that 88% of US adults have limited health literacy and 77 million Americans have difficulty attempting to use health services, obtain quality care, and maintain healthy behaviors because their health literacy is inadequate.3 Functional health literacy goes beyond proficient reading and writing; it involves the ability to accurately interpret images and oral communication provided by health care professionals.

The real question is how health literacy translates into patient outcomes. To the average person it may seem that having limited health literacy does not make a difference in things like hospital length of stay and readmission rates, but in reality, it does. Health literacy is strongly associated with patients’ ability to engage in complex disease management and self-care. Patients unable to appropriately interpret health information are more likely to be admitted for extended hospital stays, experience avoidable readmissions, and undergo unnecessary emergency care.4

In terms of preventative care, these patients typically do not understand the importance of preventative imaging such as mammograms and colonoscopies. That puts them at a higher risk of developing progressive cancers because they are not being caught early with preventative imaging.5 Health literacy is essential for patients to be able to take control and manage their own health.

Limited health literacy has been associated with nonadherence to treatment plans and medical regimens, but pharmacists play a major role in medication adherence.6 When asking if a patient is taking their medication, it is important to evaluate the reasons why they may be struggling to stay adherent. Patients with low health literacy may not be taking their medications because they do not understand their disease state or what the medication is for, even if it was already explained to them in their doctor’s office. Additionally, these patients may feel too embarrassed to disclose why they aren’t taking their medication. It is crucial that pharmacists exhibit empathy and a non-judgmental attitude in order to build trust and open space to address health literacy issues with their patients.

Strategies to Enhance Health Literacy Across Pharmacy Practice Settings

As pharmacists it is our responsibility to create an environment that is easy to navigate for patients with limited health literacy. This entails using “universal precautions,” or steps taken to interact with patients in a clear and simple way by keeping in mind that all patients might have some level of difficulty understanding health information, regardless of their education level.7 Universal precautions include using patient friendly visuals, repeating important information, using the teach-back technique, and welcoming questions. For example, rather than ending a counseling session by asking the patient “Any questions?” pharmacists can use open-ended questions that prompt teach-back:

- “I’m hoping this information isn’t too overwhelming, but can you walk me through the steps on how to administer your new medication?”

- “If you don’t mind me asking, would you be willing to explain to me how you will take your new medication?”

- “To make sure I was clear in my explanations, would you please explain what side effects you will look out for after you start your medication?”

Health information can be daunting to patients and health care providers often use medical jargon that is like a foreign language to our patients. Using simple language when counseling or explaining a patient’s medication can sometimes be the difference in determining patient adherence. For example, use “swallow” instead of “take” or “administer,” or use analogies to explain how a diuretic works rather than just mentioning “You’ll be started on a water pill.”Patients often will smile and nod during a counseling session on a new injectable or oral medicine, but this should be taken as a sign of agreement or understanding. It is important to provide an opportunity for patients to “show-back” their learning by allowing them time to physically demonstrate how they will administer their insulin or use their inhaler.

This is also a place where visual aids can be helpful. Visual aids and picture-based education sessions can have some of the most profound impacts. Some patients will have language barriers, have trouble reading a prescription label, or struggle understanding instructions. This is where visual aids can help knock down that barrier and lend itself to more impactful communication.

Many patients may leave their clinic appointments or hospital stays confused about their diagnosis or why they are having to take 3 new pills twice a day. Asking the 3 prime questions can be a launching point for identifying gaps in understanding and can have profound effects on a patient’s adherence and comfortability. These questions are:

- “What did your doctor tell you the medication is for?"

- "How did your doctor tell you to take the medication?" and

- "What did your doctor tell you to expect?”

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) created aHealth Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit to serve as a guide for health care professionals to better understand how practicing with accessibility in mind can improve patient outcomes. In addition to communicating effectively, considering how cultural and religious beliefs might influence a patient’s health view is also important. Practicing cultural humility by asking patients about their beliefs and customs and employing trained medical interpreters for support can help integrate these principles into everyday practice.

Using Health Literacy Assessment Tools

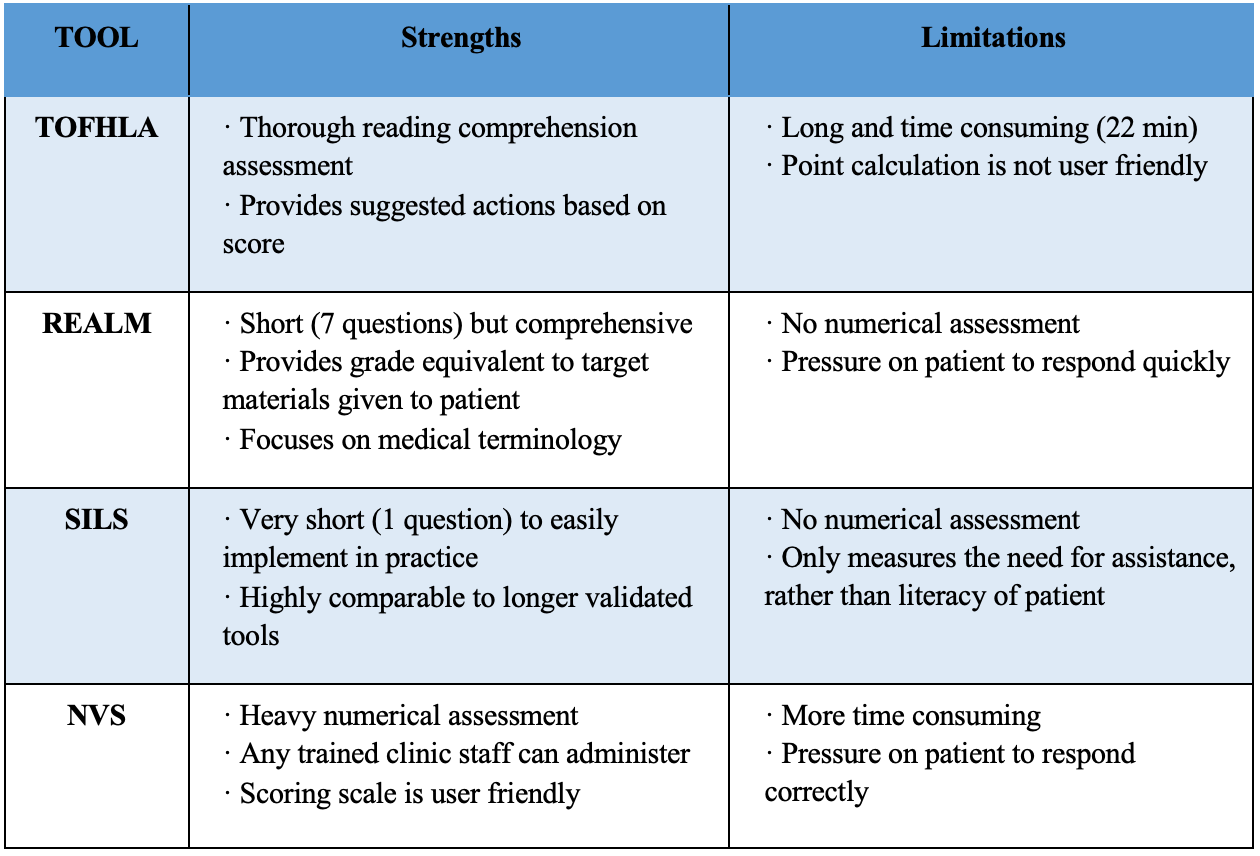

There are several tools comprised of short questionnaires that provide an idea of a patient’s health literacy level. These tools can be focused on reading, writing, or numerical aspects of health comprehension. Their versatility allows them to be used in any health care setting. Some common tools include the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), Single Item Literacy Screener (SILS), and Newest Vital Sign (NVS). REALM is a short word recognition test in which the score is correlated to a grade level (third grade to high school) to give providers an idea of what information the patient will understand.7 TOFHLA focuses on word recognition and narrative comprehension skills.8 SILS is a 1-question test to identify patients in need of help with printed health information.9 Lastly, NVS is a tool created by Pfizer to test literacy in both words and numbers.10 Refer to the table below for a quick comparison of these validated tools.

When making clinical decisions, pharmacists look to resources and guidelines to support our decision. In the same way, we must also use this mindset when health literacy is an obstacle. There is no single answer to effectively overcoming this obstacle. The Health Literacy Tool Shed from Boston University offers a variety of other resources that address specific medical conditions or populations.8 Some include the Diabetes Numeracy Test (in multiple languages), 6-Item Cancer Literacy Scale (available for different cancer types), Medication Literacy Measures, and Mental Health Knowledge.

As pharmacists, becoming aware and comfortable with these tools will strengthen our ability to relay information to our health care counterparts, thereby promoting collaboration and equitable patient care. Providers who are sensitive to health literacy have contributed to positive quality improvement across various institutions. These tools serve as a great way to start implementing foundations of health literacy into patient care.

References

- Cutilli C. C., Bennett I. M. 2009. Understanding the health literacy of America. Results of the National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Orthopaedic Nursing, 28, 27–32.

- “Improving Health Literacy.” Improving Health Literacy, 13 Feb. 2018, www.who.int/activities/improving-health-literacy.

- AMA Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, 1999. “Health Literacy:Report of the Council on Scientific Affairs.” JAMA, 281(6): 552–57. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.6.552

- Liu C, Wang D, Liu C, Jiang J, Wang X, Chen H, Ju X, Zhang X. What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Fam Med Community Health. 2020 May;8(2):e000351. doi: 10.1136/fmch-2020-000351. PMID: 32414834; PMCID: PMC7239702.

- Yılmazel, Gulay. “Health Literacy, Mammogram Awareness and Screening Among Tertiary Hospital Women Patients.” Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education vol. 33,1 (2018): 89-94. doi:10.1007/s13187-016-1053-y.

- Miller TA. Health literacy and adherence to medical treatment in chronic and acute illness: A meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2016 Jul;99(7):1079-1086. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.020. Epub 2016 Feb 1. PMID: 26899632; PMCID: PMC4912447.

- AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. AHRQ. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/index.html. Published September 2020. Accessed December 20, 2022.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services NIof H. Health Literacy Tool Shed. https://healthliteracy.bu.edu/s-tofhla. Published December 2022. Accessed December 20, 2022.

- What is the single-item literacy screener (SILS) questionnaire? CODE Technology | We Collect Patient Reported Outcomes. https://www.codetechnology.com/blog/single-item-literacy-screener-sils-questionnaire/. Published November 22, 2022. Accessed December 20, 2022.

- The newest vital sign. Pfizer. https://www.pfizer.com/products/medicine-safety/health-literacy/nvs-toolkit. Published 2022. Accessed December 20, 2022.

Newsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.