Article

Patient Navigation in the Specialty Pharmacy Space

Author(s):

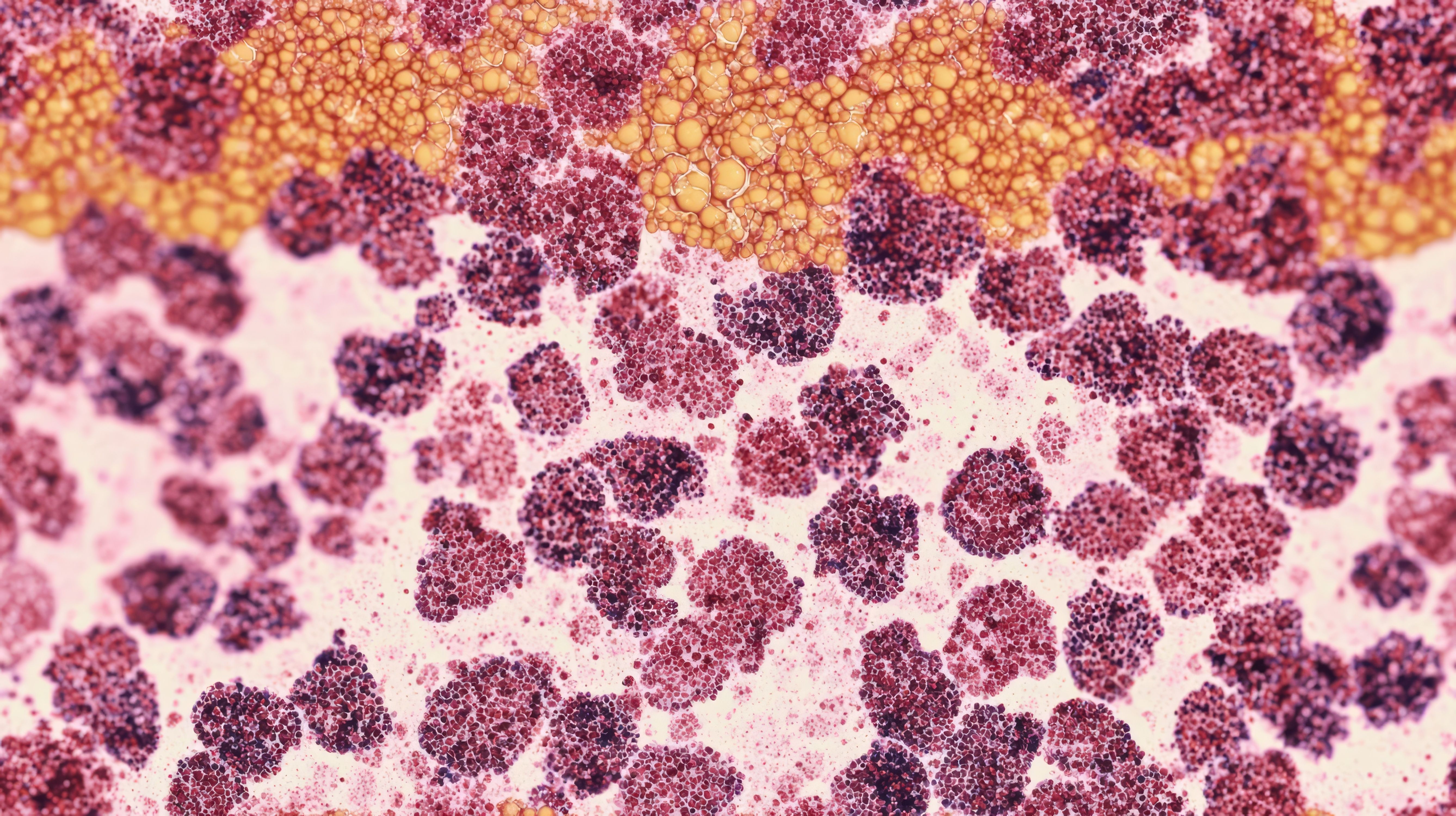

Lack of access to novel therapies, especially within the cancer space, initiated the road to patient navigation.

Within the past decades, our understanding of the positive impact of patient navigation programs has grown. Witnessing the various forms it can take and the many different professionals who give patient navigation a voice, patient navigation continues to be a sound way to close the disparities in health care access and, as the authors of a study published in the journal Cancer put it, “a strategy to improve outcomes.”1

The goal of patient navigation has remained steadfast: “to facilitate timely access for all [emphasis added] to quality standard care in a culturally sensitive manner.”2

Often targeting underserved and more vulnerable communities, patient navigation programs have evidenced better outcomes as a result of improved screenings in diseases such as cancer, adherence to follow up visits, and shortened timelines for therapy and intervention starts. After diagnosis and after an intervention or therapy decision is made, the access point to that timely therapy is the specialty pharmacy.

And the barriers to that care are there, waiting: step therapy, prior authorization, drug formularies, co-pay accumulator adjustors, and, not to be forgotten, the high out-of-pocket-cost of expensive therapies. To reduce disruptions in treatment access, specialty pharmacies should consider embracing patient navigation as the next evolution in the patient care continuum.

Several sources define patient navigation differently and with subtle nuances. An article in Cancer calls it “a patient-centric health care service delivery intervention.”3

A piece in Preventative Medicine Reports notes, “Patient Navigators are trained, lay health workers who guide patients in overcoming barriers to health care access and utilization.”4

Another article writes that patient navigation is “individualized assistance offered to patients, families, and caregivers to help overcome health care system barriers and facilitate timely access to quality health and psychosocial care.”5

What does stay certain within these variances, however, is the centrality of the patient in the equation, the goal for overcoming obstacles to care, and patient navigation as the link to reducing those barriers to care for the patient. Lack of access to novel therapies, especially within the cancer space, initiated the road to patient navigation.

Within his Harlem clinic in 1989, Dr Harold Freeman launched a landmark study on breast cancer sufferers and uncovered a 5-year survival rate of just 39% prior. After instituting a patient navigation program, the 5-year survival rate rose to 70%. Patient navigation ensured timely diagnosis and access to available therapies, and its success is evident in the jump in the 5-year survival rate.

Freeman observes, “Disparities occur when beneficial interventions are not shared equally by all.” He continues, “These findings suggest that […] there is a disconnect between what we know and what we do for all people.”6

To rephrase Freeman, underserved, often minority patients were not getting access to the latest proven therapies. Thus, patient navigation as an important tool in health care was born.

Patient navigation programs are led by peers, non-medical or medical professionals who assist patients to coordinate support across the health system, which can include education, removing financial and other barriers to care, assisting with insurance coverage, facilitating access to community resources, and providing emotional support.7

The reality for patients is that access to timely therapies hits roadblocks every day. Given that 82% of surveyed patients reported delays in accessing meds, a clear problem exists. Today, chief among these delays are insurance issues and costs associated with medications.

Sadly, these barriers result in anxiety, depression, and insomnia that often must also be treated. CoverMyMeds reports that 66% of patients experienced anxiety and depression symptoms as a consequence of delays in their therapy, and 54% of those, as a result, started taking medication in addition to their prescribed, but delayed therapies.8

One can see how a navigable snag may quickly become a serious impediment. Moreover, more than one-third of patients reported sacrificing meds due to these barriers.8

Pharmacists and their employees have observed these obstacles and witnessed the fragmentation of the health care system into compartments that do not always work well together. As a quintessential player in patient care, they have responded and positioned themselves as a patient navigation resource whether they wear that job description or not.

According to CoverMyMeds, a staggering 84% of pharmacists and pharmacy staff help with benefits information within a given week. This goes well beyond simply running insurance and includes helping patients navigate co-pay accumulators, understand out-of-pocket resources, and find assistance.8

More than half of pharmacists surveyed indicated spending 1-2 hours with patients, especially when it involves complex medications.8 An article in the Journal of the National Medical Association confirms this, noting in their study of patient navigation programs that an average of 2.5 hours per patient was spent helping patients reduce barriers to care.9

With the pharmacy as a resource, patients are indicating that their sense of this relationship has changed, and they rely on pharmacy and their staff more. In other words, it is no longer simply about picking up medication.

More than one-third of patients surveyed by CoverMyMeds indicated using their pharmacy to explain benefits and payment in addition to or sometimes over the insurer. Another third consult their pharmacist to gather additional information on their condition and its treatment. Many of the patients also use their pharmacy for services unrelated to their immediate medication and care.10

Even beyond the insurance and out-of-pocket costs, which rank as the top blocks to access to care, patients highlight the emotional support needed and received via patient navigation programs. Relationship-building thus forms another root in the success of patient navigation programs.

As one researcher notes, relationships between patient and navigator influenced the outcome, adding, “The process of [patient navigation] has at its core relationship-building and instrumental assistance.”11

The success of patient navigation is shown to also depend on the people involved. A study that examined a broad mix of patient navigation programs concluded, “The type of navigator used was not found to affect patient outcomes.”

The programs studied utilized lay persons, nurses, clinicians, and physicians and indicated that the ability at relationship-building was the key determinant for a patient’s success.

“A common theme in each of these studies was the need for emotional or social support from the navigator,” the authors wrote.12

Formalizing that process, establishing an official patient navigation program within the pharmacy, seems the natural progression in this synergetic relationship. It also is another gap to close in the disparities which yet exist in health care.

Patient navigation programs have proven themselves a gateway to improved outcomes. Patients are also being more proactive and seeking avenues to gain the access to care, with 90% of those surveyed saying exactly that.8

Specialty pharmacies should assume a more vital role in the care continuum and welcome patients in working together to gain access to the care and medication all patients deserve.

About the Author

Shelby Smoak, PhD, is an advocate and education specialist for BioMatrix.

References

- Freedman, Harold M., and Rian L. Rodriguez. “History and Principles of Patient Navigation.” Cancer. 10 July 2011. https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cncr.26262

- Freeman, Harold M. “The Origin, Evolution, and Principles of Patient Navigation.” Cancer, Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Prevention. 21.10 (2012). https://aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/21/10/1614/69026/The-Origin-Evolution-and-Principles-of-Patient

- Freedman, Harold M., and Rian L. Rodriguez. “History and Principles of Patient Navigation.” Cancer. 10 July 2011. https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cncr.26262

- Wang, Monica L., et. al. “Navigating to Health: Evaluation of a Community Health Center Patient Navigation Program.” Preventative Medicine Reports: 2 (2015). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211335515001047

- Kline, Ronald M., et. al. “Patient Navigation in Cancer: The Business Case to Support Clinical Needs.” Journal of Oncology Practice. 15:11 (2019). https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JOP.19.00230

- Freedman, Harold M., and Rian L. Rodriguez. IBID.

- McBrien, Kerry A., et al. “Patient Navigators for People with Chronic Illness.” PLOS One. !3:2 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5819768/pdf/pone.0191980.pdf

- Cover My Meds. “2022 Medication Access Guide.” PDF.

- Lin, Chyongchiou J., et. al. “Factors Associated with Patient Navigators’ Time Spent on Reducing Barriers to Cancer Treatment.” Journal of the National Medical Association. 110.11 (2008). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0027968415315078

- Cover My Meds. “2022 Medication Access Guide.” PDF..

- Jean-Pierre, Pascal., et al. “Understanding the Processes of Patient Navigation to Reduce Disparities in Cancer Care: Perspectives of Trained Patient Navigators From the Field.” Journal of Cancer Education. April 2010. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13187-010-0122-x

- McVay, Sheri., et. al. “The Effect of Different Types of Navigators on Patient Outcomes.” Journal of Oncology. April 2014. https://www.jons-online.com/jons-categories?view=article&artid=3665:the-effect-of-different-types-of-navigators-on-patient-outcomes&catid=18

Newsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.

2 Commerce Drive

Cranbury, NJ 08512

All rights reserved.