Article

Gray Matter Degeneration Linked to Multiple Sclerosis Disability

Author(s):

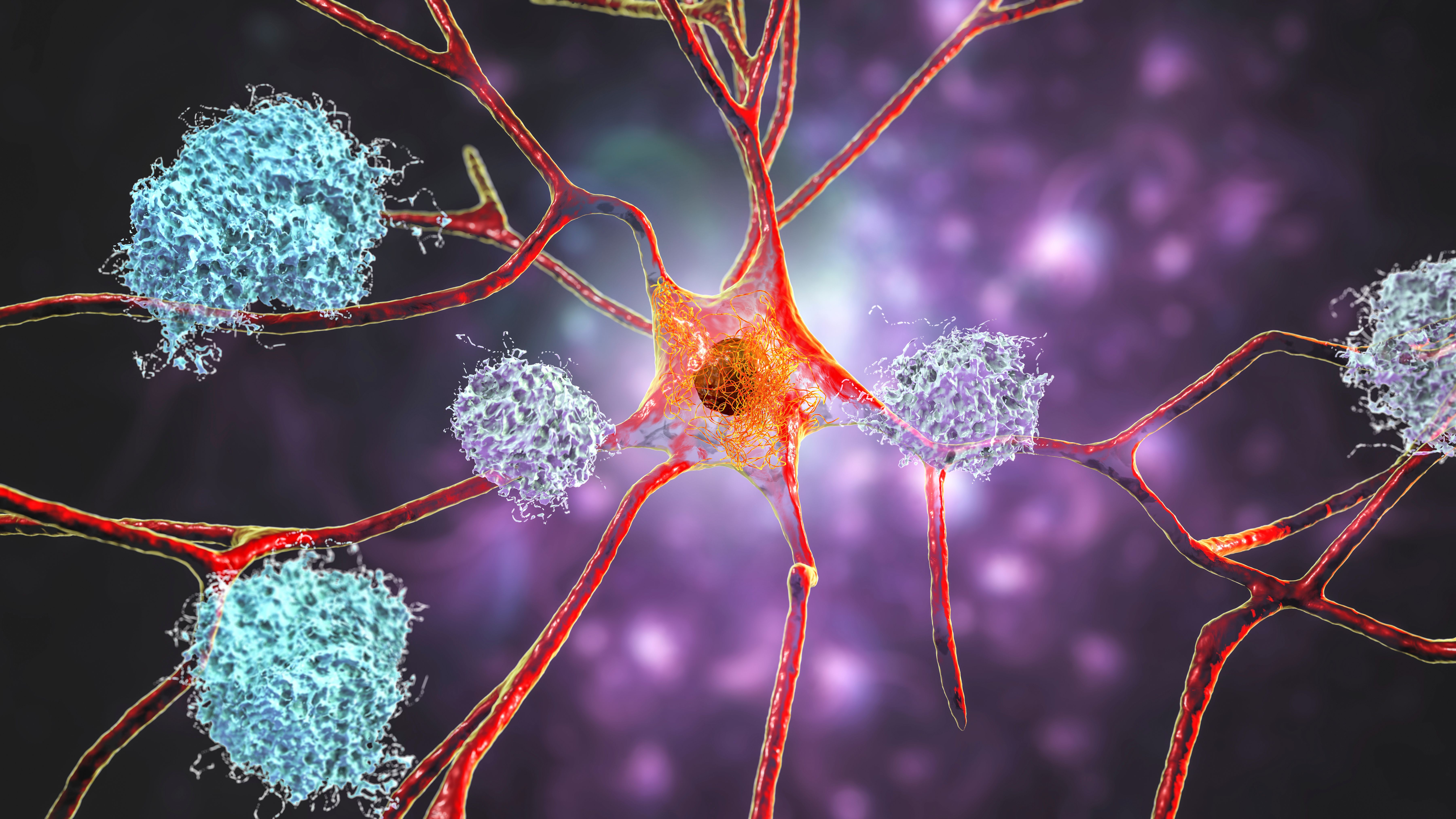

A more detailed look at gray matter atrophy may hold clues to multiple sclerosis progression.

A link between a pattern of brain tissue loss and multiple sclerosis (MS) disability was recently discovered, according to a study published by the Annals of Neurology.

The new research is one of the largest brain imaging studies conducted in MS and could result in better and earlier prediction of MS-related disability progression.

“It’s well known that brain atrophy occurs in people with MS and varies by region, but we typically only measure the shrinkage of the whole brain,” said lead author Arman Eshaghi, MD. “By looking at brain tissue loss in a more detailed fashion in different MS subtypes, we found it’s possible to predict disability progression in advance. This has many implications in clinical trials that use brain atrophy to investigate the effect of neuroprotective drugs.”

Retrospective data were collected from 7 research centers across 5 countries that were involved with the MAGNIMS consortium. The data included MRI scans and disability measures from 1214 patients with MS and 203 control patients without MS.

The data showed that the loss of deep gray matter volume was faster than the loss of other regions of the brain.

Related Coverage: OTC Allergy Drug May Restore Nerve Cell Signaling in Multiple Sclerosis Patients

Notably, there was a link found between gray matter volume loss and disability. The most significant link was observed with loss in the thalamus, which has the largest amount of gray matter and controls sensory and motor signals, according to the study.

The authors also discovered several spatial patterns of gray matter loss, including those specific to different types of MS. This is the first time these specific changes have been identified, according to the study authors.

Regions deep within the brain that have many connections were found to be more vulnerable to degeneration than other regions less deep in the brain, according to the study.

The findings also suggest that ongoing brain atrophy is contingent on the subtype of MS, which has significant implications for future drug development, according to the authors.

“Our methods could be used right away for phase 2 clinical trials, offering up a higher sensitivity than existing measures to investigate whether a new drug could work,” Dr Eshaghi said.

However, the authors warn that the method cannot predict disability progression in individual patients. Instead, it may be useful at a population level and could support clinical trials of treatments that protect nerve cells, according to the study.

“We have demonstrated that deep grey matter atrophy is linked to disability progression in multiple sclerosis by using advanced imaging analysis techniques and collecting a large number of MRI scans, because of the effort of many European researchers,” said senior author Professor Olga Ciccarelli, PhD.